Allergic Conjunctivitis

Q: What are the causes of red eye?

A: The commonest causes of red eye are

- Infective conjunctivitis

- Allergic conjunctivitis

- Uveitis

- Acute angle closure glaucoma

- Dry Eyes

- Many many more……

Q: What is allergic conjunctivitis?

A: Eye allergies are also called “allergic conjunctivitis.” It is a reaction to indoor and outdoor allergens (such as pollen, mold, dust mites or pet dander) that get into your eyes and cause inflammation of the conjunctiva, the tissue that lines the inside of the eyelid and helps keep your eyelid and eyeball moist. Eye allergies are not contagious.

Q: How common is allergic conjunctivitis?

A: 60 % of the general population have some form of allergy. The numbers are higher in metros and cities. 20 % of the general population have eye allergy. Approximately 4 percent of allergy sufferers have eye allergies as their primary allergy, often caused by many of the same triggers as indoor/outdoor allergies. For some, eye allergies can prove so uncomfortable and irritating that they interfere with job performance, impede leisure-time and sports activities, and curtail vacations.

Q: What causes eye allergies?

A: Allergens are what trigger your eye allergies. To the body, allergens are considered foreign substances that threaten or irritate the body, such as pollen from ragweed or cat dander. If you react to certain allergens, this means your eyes have become sensitized at some point. Therefore, when your eyes come into contact with specific allergens, an allergic response results.

Eye allergies are grouped in various ways, one of which is where the allergens are located—indoors or outdoors. Some allergens are more likely to be found indoors. Others you’re more likely to be exposed to outdoors.

INDOOR ALLERGENS Examples of common indoor allergens that may cause itchy eyes are airborne cat dander and dust mites.

OUTDOOR ALLERGENS Examples of common outdoor allergens that often trigger itchy eyes are grass, tree, and ragweed pollens.

Other substances called “irritants” (such as dirt and smoke, chlorine, etc.) and even viruses and bacteria, can compound the effect of eye allergies, or even cause irritation symptoms similar to eye allergies for people who aren’t even allergic. The eyes are an easy target for allergens and irritants because, like the skin, they are exposed and sensitive. Certain medications and cosmetics can also cause eye allergy symptoms. By way of response to these allergens and irritants, the body releases chemicals called histamines, which in turn produce inflammation.

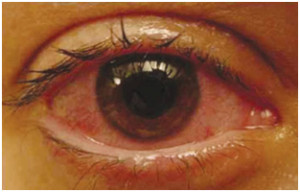

Q: What are the signs of eye allergy?

A: The common symptoms of eye allergies are the result of this inflammation:

- Redness

- Itching

- Burning

- Tearing or watering

- Swollen eyes

- Gritty sensation in the eyes

- Intolerance to contact lenses

These symptoms may be accompanied by a runny or itchy nose, sneezing, coughing, or a sinus headache. Many also find that their vision is temporarily blurred, or that they feel distracted, unproductive, or tired.

Q: I have these symptoms all through the year? Can it still be allergic conjunctivitis?

A: There are two types of allergies.

- Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: In this type eyes are affected only in a particular season. Summer, winter or wet season depending on the cause of allergy (allergen)

- Perennial allergic conjunctivitis: In this type eyes are affected throughout the year. This kind is similar to other severe forms of allergy like Bronchial Asthma. It is common in children. Also people having this form of allergy have some other severe allergic conditions like skin allergy (atopic dermatitis) or allergic bronchitis or Asthma.

So, allergy can recur throughout the year. However the eyes have to examined to rule out other causes of red eye especially uveitis.

Q: Can children have allergic conjunctivitis?

A: Yes. Infact allergic conjunctivitis is very common in children, similar to tonsillitis or adenoids. It commonly persists till about 15 years of age and then in majority of patients it subsides thankfully.

Since the course is chronic, children have to be treated carefully, making sure the side- effects of medication don’t damage the eyes. So self medication is not advisable, not just in children but even in adults.

Q: How are eye allergies treated?

A: The best defense against allergic conjunctivitis is to first avoid contact with substances that trigger your allergies. When prevention is not enough, consider over-the-counter or prescription treatments. Eye allergy symptoms may disappear completely, either when the allergen is removed or after the allergy is treated.

- Oral medication

Oral anti-histamines are crucial apart from eye medications. Till overall allergy is treated, ocular allergy is not going to subside completely.

- Eye medication

- Ocular medications like anti-histamines and NSAIDs help in controlling the ocular allergy to certain extent.

- Lubricants help in washing away the allergens and the toxic inflammatory material.

- In some severe cases, mild steroid eye drops are needed to treat the allergy.

Q: Can allergic conjunctivitis cause vision loss?

A: In majority of cases it does not cause vision loss. However in severe cases, it can cause corneal ulcers, which if untreated can cause vision loss.

Q: How to prevent allergy?

A: Eye allergy can be prevented by:

- Don’t touch or rub your eye(s).

- Wash hands often with soap and water.

- Wash your bed linens and pillowcases in hot water and detergent to reduce allergens.

- Avoid wearing eye makeup.

- Don’t share eye makeup.

- Never use another person’s contact lenses or misuse contact lenses

Q: Can contact lens cause allergy?

A: For contact lens wearers, eye allergies can cause unique problems. During allergy season, there are many loyal contact lens wearers who revert back to their eyeglasses due to discomfort. But many others develop strategies that allow for daily lens wear in comfort and ease. And as for those with allergies who think they cannot wear contact lenses – the fact is many of them can.

In the past, contact lens wearers have been interrupted by allergies, especially seasonal allergies, causing some to discontinue lens-usage, and others to stop considering contact lenses as an option. But some of today’s contact lenses are far more accommodating for people with allergy-related eye conditions. In addition, they are available in multiple modalities, including daily disposable and two-week replacement. Your doctor will direct you to the right lens for your vision and lifestyle needs. Replacement wear lenses require maintenance—cleaning and disinfecting every day after removal—as proteins, allergens, and lipids cling to their surface. These can cause discomfort, particularly for allergy-sufferers.

Smart Strategies for Contact Lens Wearers

Here are some strategies that doctors recommend:

- Limit wearing time.

- Make your own allergy-season “paradigm shift,” by wearing your lenses part-time, for example, for sports, social events (e.g., weddings and proms), and photos with family and friends.

- Use daily wear, two- or four-week replacement contacts.

- Use eye drops as prescribed by your doctor.

Studies have shown that single-use contact lenses can be a healthy option for contact wearers in general, including for some people with eye allergies.

Amblyopia (Lazy Eye)

Q: What is Amblyopia?

A: When a young child uses one eye predominantly and does not alternate between the two eyes, the prolonged suppression of the nondominant eye by the brain may develop into amblyopia. Amblyopia is sometimes referred to as “lazy eye,” but it is more than just an eye problem. The visual portion of the brain is suppressed and vision actually decreases in the unused eye.

There are different causes of amblyopia:

- Misalignment of the eyes with one eye not being used properly

- A need for glasses that has not been corrected

- Glasses are needed because one eye is out of focus

- The presence of a cataract (an opacity of the lens inside the eye) that distorts light images from properly focusing on the back of the eye, preventing good vision from developing for that eye

- A droopy or enlarged eyelid that covers the pupil and blocks the vision in that eye

In some cases there may be more than one cause.

Q: How is amblyopia treated?

A: Amblyopia (“lazy eye”) is by far the greatest cause of treatable vision loss in India. A child with amblyopia may lose vision in the affected eye permanently if the situation is not corrected early. Treatment is more difficult and less effective with children older than 9 or 10 years of age.

If your child is diagnosed with amblyopia, an individual active treatment program will be designed. This program may involve one or more of the following: eyeglasses, patch therapy, eye drops that dilate the pupil, and in some cases a contact lens. Your ophthalmologist will give you specific information about the treatment for your child.

Q: Won’t eyeglasses help?

A: In cases where child has high refractive error (high power glasses) and child has never used one, appropriate glasses can help the child see well. However glasses alone don’t help, other treatments have to be given to treat amblyopia.

Q: What about contact lenses?

A: In children who have a significant difference in the refractive error (power) between two eyes as a cause of amblyopia, contact lenses can be tried in the eye with higher error along with other amblyopia treatment.

However it needs proper hygiene and good child cooperation, which in most cases cannot be possible. Hence contact lenses are given only in select cases. Glasses are preferable.

Q: What is Occlusion (Patch) Therapy?

A: In order to improve your child’s vision, you may be instructed to patch an eye. Patching is a common method of treatment for the various types of amblyopia. This type of visual loss cannot be corrected by glasses alone or with surgery. The treatment is effective when it forces the child to use the “lazy eye” by patching the good eye. Patching is most effective in young children, but can also help improve vision in the early teen years. Untreated, amblyopia cannot be reversed, and the visual loss becomes permanent. Clear instructions, reasonable expectations, patience and consistency are all part of the comprehensive approach to your child’s eye care.

Q: How does my child adjust to the patch?

A: All children who are patching have similar problems. It is uncomfortable and sometimes difficult to adjust to wearing a patch. Your child may not see well at first, and this can be frightening. However, it does not hurt, and it does not damage your child’s normal eye. It is the best thing to do to preserve vision for a lifetime. For that reason, it is important that your child wear the patch as directed. (You will receive instructions on how often to patch your child.)

Q: Will the patching not damage the skin?

A: The patch must be of an adhesive type that sticks to the face. A “pirate patch” with strings or elastic is NOT advised. Be sure that the patch sticks firmly to the skin for the duration of patching time. The narrow end of the patch is placed toward the nose and the broad end away from the nose.

Patches come in regular and junior sizes and may be purchased at drug stores.

Although eye patches are hypoallergenic, some children develop mild skin irritation from wearing the patch. The broad area can be trimmed with scissors so that less adhesive contacts the face. The patch may be rotated slightly so that the same part of the skin is not always under the adhesive. To protect the skin and decrease irritation, you may apply Milk of Magnesia with a cotton ball to the skin area where the patch will stick and allow it to dry completely. Be careful not to get Milk of Magnesia into the eye. Then apply the eye patch as usual.

Q: How to remove the patch?

A: Removing an adhesive eye patch can be uncomfortable and distressing to the parent and child. Try to remove the patch slowly while applying pressure to adjacent skin to lessen pulling. Soaking the patch with cool water before removal is also helpful. Another method is to rub petroleum jelly or vaseline into the adhesive portion of the patch. Let the petroleum jelly soak in for about 30 minutes before gently pulling off the patch. The skin surrounding the patched eye can be treated with any skin care product to lessen skin irritation. Avoid getting any product into the eye.

Q: What to do if my child removes the patch?

A: If your child removes the patch before the full amount of time that he/she is supposed to wear it, immediately replace it with a new patch. Refocus your child’s attention with a toy or game in order to help to distract him or her from awareness of the patch. Be persistent. Since the patch is not painful, most children will wear the patch once they realize that their parents intend for them to wear it, and that it will be replaced. Young children can be discouraged from removing the patch by placing them in mittens or pediatric arm restraints.

Q: What to do after patching?

A: While your child is wearing the eye patch, he/she should be encouraged to use the other eye as much as possible. To shorten the patching period, encourage your child to participate in detailed busy work such as paint-by-numbers, connect-the-dot books, colouring, writing, drawing and tracing.

Some slight redness of the eye is common because children frequently rub the eye or the patch. Extreme redness, accompanied by discharge, should be reported immediately to your eye doctor. If at any time during the patching routine your child contracts measles, chicken pox, poison ivy, or any other type of skin eruption around the eye, DISCONTINUE the patching.

Q: What is the effect of the patch on the better eye?

A: If the cause of amblyopia is a squint, then sometimes the deviation seems to switch eyes or get worse with the patch. This is normal and only means that the “lazy eye” is now being used so that it stays straight while the other eye turns. This indicates that the patching program is having an effect. Improving vision in the weaker eye is the first step. The deviation can be dealt with when the lazy eye’s vision has recovered. Keeping return visits is important so any changes can be tracked.

Q: How long will my child need to wear the patch?

A: Patching will be continued until there is no further improvement in visual activity or until your child uses one eye equally as well as the other. It is impossible to predict how long this will be for each child, but it typically lasts for several months with some less intense patching thereafter. Patching could be one of the most important steps in the treatment of your child’s eye condition. Do not become discouraged! No matter how difficult it may seem, the long-term results are well worth it.

Q: What if my child must wear the patch while at school?

A: Some children will need to wear the patch at school or at the day care facility. If your child removes the patch frequently at home, this will probably also happen at school. Make sure your child’s teachers understand the importance of the patch. Provide them with extra patches so they can be replaced at school when needed.

Please help your older child to deal with the comments that others will make about the patch. Just as a leg plaster and crutches help while a broken bone is healing, the eye patch is a short-term way of helping your child to have better vision for life. Practice an answer to any questions that will satisfy the questioner and make your child feel positive about the process. For example, when asked “What is that on your eye?” the response could be “It’s a patch to make my weaker eye stronger.”

Q: What is Atropine Treatment for amblyopia?

A: Atropine drops may be used to treat your child’s amblyopia. Atropine blurs vision in the better-seeing eye and encourages use of the eye with poor vision and improves vision in that eye over time. Atropine may be used in addition to or as an alternative to traditional patching therapy. Because atropine cannot be removed once applied, it is a good treatment option.

Q: How to apply the drops?

A: Have your child lie down on his/her back, looking up at the ceiling. Hold the eyelids apart and let one drop fall anywhere between the eyelids. If the child is frightened, try giving the drop before he or she wakes up. In some children, it is necessary for one adult to hold the child while the other gives the drop. Eventually a routine will be established. Be sure to wash your hands after applying the drop so that you do not accidentally get any medication into your eyes. Also, take care not to get any of the drops in your child’s other eye.

Q: What to expect from the drops?

A: Unlike other types of eye drops, atropine usually does not sting. These drops cause the pupil (black center of the eye) to become very large. Your child may notice that close objects are blurred. This is the normal effect of the drops and may last for up to a week following one drop of atropine. Your child may also be bothered by bright sunlight. Sunglasses or a broad-brimmed hat may be worn outdoors on sunny days to avoid discomfort.

Since atropine blurs the vision of the better eye for near work, this forces the child to use the weaker eye for reading, drawing, etc. Allow your child to hold reading material close or to lean close to the desk. If your child attends school, please notify his/her teacher of the eye treatment. In some cases, reading glasses may be prescribed for using the better eye while at school.

Q: What are the side effects of atropine?

A: Rarely, a child may develop redness and swelling around the eye, fever, or a red warm face and neck. If this occurs, STOP using the drops and contact our clinic. Be sure to keep the atropine drops out of the reach of children. If a child drinks atropine from the bottle, contact your paediatrician immediately. It is an emergency.

Q: How long do I continue giving the drops?

A: Atropine treatment may be continued for weeks or months, depending on your child’s age and the severity of the vision loss in the amblyopic eye. Keep using the drops as instructed until the next appointment day unless your doctor says differently.

Q: Will my child’s vision improve with surgery?

A: Many patients who have amblyopia due to squint will eventually need an operation to align the eyes called squint surgery.

In cases of cataract or lid drooping, surgery is required to remove the cause of amblyopia followed by patching, glasses or both. Surgery alone will not improve your child’s vision.

Other causes of amblyopia will not require surgery.

Q: What is the prognosis?

A: Most cases of amblyopia do well if compliance with treatment is good. Majority of children will have good enough vision to do normal activities. However it ultimately depends on age of child, severity of amblyopia and presence or absence of other co-morbidity factors.

Age Related Macular Degeneration (ARMD/AMD)

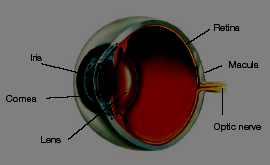

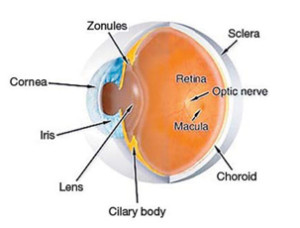

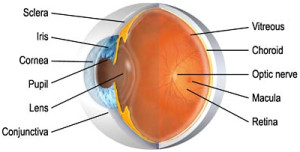

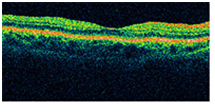

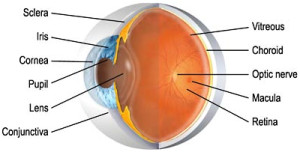

Q: How do we see?

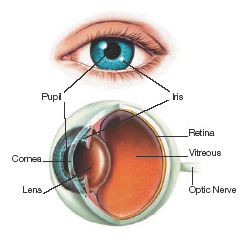

A: Our eyes are like a camera with a lens system at the front of the eye, and the retina, like a photographic film, lining the inside wall of the back of the eye. Light passes through the cornea, pupil and lens and is focused on the light sensitive retina to form an image. Messages are sent via the optic nerve to the brain for processing.

Q: What is macula?

A: The macula is the central part of the retina. It is a small, specialized area in the middle of the retina and is responsible for our ability to see fine detail. This central vision is the vision we use for reading, driving, recognising faces, threading needles and other fine detailed work. The remaining part of the retina is responsible for our side vision, also known as peripheral vision.

This is our mobility vision, allowing us to get about and to maintain our independence.

Q: What is ARMD?

A: With ARMD, there is damage or breakdown of the macula, leading to loss of central vision. The eye still sees objects to the side since peripheral vision is not affected. For this reason macular degeneration does not result in total blindness.

Q: What is Dry ARMD?

A: The most common form of the disease is known as Dry ARMD. This form occurs in approximately 80 to 90% of people with ARMD.

Q: How severe is it? How does it affect my vision?

A: In Dry ARMD the vision loss is usually very gradual and is seldom severe. Areas of the central retina gradually become thin and stop working. Some people notice blank areas in their vision.

Q: How can I prevent or cure it?

A: Vitamin supplementation, diet modification and stopping smoking can all decrease the rate at which this gets worse, and the eyesight may also be helped somewhat with the use of special low-vision magnifying lenses.

Q: What is Wet ARMD?

A: Some people develop a more aggressive form of the disease called Wet ARMD that can lead to rapid and severe vision loss. This occurs in only 10 to 15% of people with macular degeneration. In Wet ARMD, abnormal blood vessels grow under the macula and eventually leak fluid, bleed or lift up the retina. When this happens central vision is reduced and often distorted. The longer these abnormal new vessels continue to leak, bleed and grow, the more central vision will be lost.

Q: Will I become blind?

A: Left untreated, these fragile vessels will cause scarring and irreversible loss of the detailed central vision. Sometimes only one eye loses vision while the other eye continues to see well for many years. If both eyes are affected however, reading and close-up work may become extremely difficult. It does not cause blindness and since the side vision remains, people can usually take care of themselves quite well.

Q: What are the symptoms of Macular Degeneration?

A: Most patients with ARMD will notice difficulty in reading as words become blurred or crowded. There may be a black or grey spot in your central vision. A frequent and important early symptom of Wet ARMD is distortion when straight lines appear bent or wavy. You may become aware of this when looking at a page of small print or looking at a window frame or telephone pole with your affected eye.

These changes in eyesight are important symptoms and if they occur you should contact your ophthalmologist promptly. Do not assume you simply need a new pair of glasses and wait for an appointment in the future.

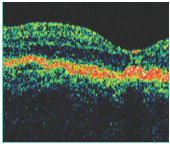

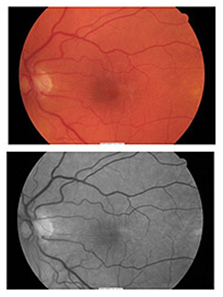

Q: How is ARMD diagnosed?

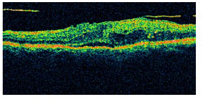

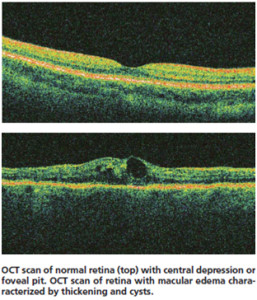

A: Many people do not realize they have macular problems until blurred vision becomes obvious. An eye specialist can examine the macula and identify early changes. If Wet ARMD is suspected, special tests called optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiogram are usually required.

OCT is a no-touch method of scanning the macula to look for fluid leaks, the first sign of Wet ARMD. It only takes a minute to do, and no needles or touching of the eye are required.

Fluorescein angiography is used to locate exactly where the leaking blood vessels are. In this test, dye is injected into a vein in the arm. The dye travels through the body, and with a special camera a series of photographs are taken as the dye passes through the retina, putting together a map of the problem which can be used by the doctor during treatment.

Q: What is the treatment for Dry ARMD?

A: With any kind of ARMD, various measures have been shown to decrease the risk of the disease getting worse. These include:

1. Vitamin Supplementation

A large American study, the Age-Related Eye Diseases Study (AREDS) found that using certain combinations of vitamins could reduce the chance of ARMD getting worse by about one quarter.

2. Stop smoking

Smokers are at higher risk of ARMD, and of Wet ARMD in particular. It is therefore very important to stop smoking at the earliest sign of this condition.

3.Dietary changes

Various foods seem to protect against the development of Wet ARMD, including nuts and fish oils.

Q: What is the treatment for Wet ARMD?

A: With Wet ARMD, several different treatments are possible:

1. Avastin/ Lucentis/ Macugen Injections

These drugs at present appear to be the best treatment for Wet ARMD. They are injected into the eye, and may need to be repeated several times over the course of several months, but they have been shown to improve vision in people with Wet ARMD, so long as scarring has not started to take place. No other treatment seems to improve vision; other treatments can only decrease the rate at which things get worse.

2.Thermal Laser Therapy (Photocoagulation)

In this procedure, the heat from a laser light is used to cauterize the abnormal leaky blood vessels. This treatment also damages overlying normal retina. This is done only if new blood vessels are away from the macula.

3. Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

PDT uses a light-activated drug (Visudyne) and a special non-thermal laser to selectively destroy abnormal blood vessels while preserving surrounding normal healthy tissue. It is used less frequently now since the injections are proven better than PDT alone.

Q: Do the injections have any side effects?

A: Like any procedure on the body, these injections also have side effects which are thankfully rare.

With any injection in the eye, there is always a risk of infection or retinal detachment, the chances of which are 0.1 %. Occasional reports of excess reaction in the eye, increase in eye pressure, episodes of stroke and heart problems have been reported. Overall these drugs are safe, highly effective and are used worldwide.

Q: How do monitor my vision?

A: Amsler Grid Eye Exam can be used at home for monitoring one’s vision.

Directions:

- Wear the glasses or contacts you normally wear for reading.

- View the grid at reading distance (approx 30cm) in a well-lit room.

- Cover one eye with your hand and focus on the centre dot with your uncovered eye. Repeat with the other eye.

- If you see wavy, broken or distorted lines, or blurred or missing areas of vision you may be displaying symptoms of ARMD and should contact your eye care provider immediately

Q: Is there no alternative to repeated injections?

A: Unfortunately not till now. Research is on in this field. Many new drugs in the form of better injections and even eye drops are in the pipeline in the near future. In fact a drug called Eyelea is already available in Europe, which shows comparable results as Avastin and Lucentis, if not better. However it may take some time to reach Indian shores.

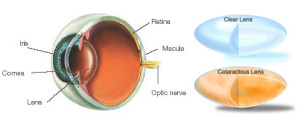

Cataract

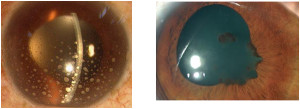

Q: What is cataract?

A: A cataract is an opacity (or cloudiness) in the lens of the eye. This cloudiness develops inside the lens and restricts light passing through the eye and reaching the retina. When this occurs,vision is affected.

An opacity can be quite minor or it can become so marked that it prevents adequate vision.

Q: What causes a cataract?

A: The most common cause of cataracts is aging. Others include:

- Inherited or developmental problems

- Health problems such as diabetes

- Medications such as steroids

- Trauma to the eye

Q: How will I know if I have a cataract?

A: People with cataract generally complain of the following-

- Cloudy or blurry vision

- Light sensitivity from car headlights that seem too bright at night; glare from lamps or very bright sunlight; or the appearance of a halo around lights

- Poor or reduced night vision

- Double or multiple vision (this symptom often goes away as the cataract progresses)

- “Second sight” where near vision becomes possible without glasses again because of the cataract developing in the lens. This state is usually temporary, and followed by progressive loss of distance vision

- A need for frequent changes of glasses or contact lenses

However only a doctor can tell you whether the above complaints are due to cataract only or something else. Other eye conditions, for example glaucoma, agerelated macular degeneration, injury and previous eye operations can also affect your eyesight.

Q: What is the treatment of cataract?

A: When a cataract is not fully formed, it may be possible to improve your eyesight with glasses. Your ophthalmologist will advise you if glasses are suitable.

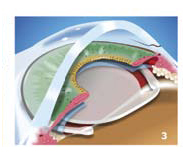

When the cataract grows too dense, glasses will not be effective and cataract surgery is necessary.This involves removing the cloudy lens from inside the eye through a small incision,and replacing it with a new artificial lens, alsocalled the Intraocular Lens (IOL) made from acrylic materials.

Q: What is an intraocular lens (IOL)?

A: It is an artificial lens, made from acrylic materials used to replace the natural lens and is implanted inside the eye during surgery.

They are broadly of two types.

- Monofocal lenses

They are the commonest types of lenses implanted in the eye since last 20-30 years. They can correct only distance vision. Glasses are required for near vision. However vision quality is very good. Monofocal lenses with Aspheric Optics (Premium Lens) results in clearer, brighter,better quality vision with enhanced contrast,most noticeable in low light conditions such as driving at dusk, in fog or drizzle, and with restaurant lighting. - Multifocal lenses

They are newer generation of lenses. They can give you both distance and near vision without glasses. However some patients may require glasses for both in spite of multifocal lenses due to variable healing response of the eye.They might give rise to glare at night especially for driving. Also vision quality in low light conditions can be affected. However with the newer lenses available, these problems occur rarely.Also not everyone can opt for multifocal lenses. There are some strict guidelines for using these lenses, which if not followed can give rise to the above problems and even more. You doctor can clarify these details with you if you need them.There are other special lenses like TORIC lenses which can be used in selected cases of high astigmatism. They require high level of expertise and generally give good results. However glasses may still be required after implanting them as well.Ultimately let your doctor decide what is best for you and which lens will suit your eye.

Q: When can one undergo cataract surgery?

A: In earlier times, cataract surgery was only done when the eyesight was very bad. Advances in technology mean that modern surgery is less traumatic to the eye. The results are more predictable, there are few side effects and the eye usually recovers quickly.Modern cataract surgery is done when people find their failing eyesight does not let them do their day today activities.

Q: Will I recover complete vision after cataract surgery?

A: Other eye conditions, for example glaucoma, age related macular degeneration, injury and previous eye operations can also affect your eyesight. Your ophthalmologist will examine your eye and advise you on the possible effects of other eye disease on the cataract surgery. In some cases eye condition scan affect the timing of surgery e.g. it may be better to delay surgery if active diabetic retinopathy is present and prepone it if corneal problems or glaucoma are present.

Q: How does one fix up cataract surgery?

A: At the consultation with your ophthalmologist, your operation can be booked within a few days. You will be checked about your medications, general health and drug allergies. Your ophthalmologist will discuss what focus you want after surgery. For example it may be possible to have your eyesight sharp for distant objects (sharp driving vision without glasses) or for near objects (sharp vision for reading without glasses). It may also be possible to have astigmatism corrected.

A laser or ultrasound machine is used to measure your eye. This gives data on the shape of the eye. From these figures, your ophthalmologist will choose appropriate lens implant to be used in your operation.

Your ophthalmologist’s staff will advise you the exact time & date of your operation.

Q: Is the surgery painful? Will I be made unconscious?

A: You will be asked to report one hour before the scheduled operation time. Drops will be put into the eye to dilate the pupil. Local anaesthetic is used to numb the eye. The local anaesthetic is given as an injection. In the operating theater you will be awake under a sheet. An instrument holds your eye open so you do not have to worry about blinking. The operation takes about 10-30 minutes. After the operation you may have a pad on your eye overnight. More detailed instructions will be given to you after your operation.

Q: What are the risks of surgery?

A: All surgery, no matter how technologically advanced, carries risk. Minor complications can lead to extra appointments or medications after the operation. In some cases, extra operations are needed. Complications can delay the recovery of your eyesight after surgery. Minor complications usually do not cause loss of eyesight. Serious complications such as infection and bleeding in the eye can cause loss of eyesight. Fortunately, serious complications are rare. Your surgeon will discuss with you the potential benefits versus the potential risks of cataract surgery.

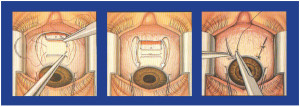

Q: What surgical technique is used?

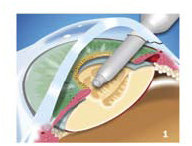

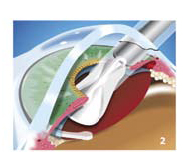

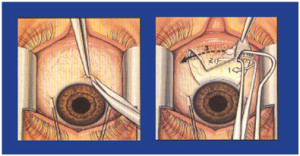

A: All surgeries are done with the latest “Phacoemulsification” technique through a very small 3 mm incision. It uses ultrasound power (misunderstood as LASER by general public). The steps are illustrated below.

Q: What are the precautions one has to take after surgery?

A: Surprisingly, there are no major restrictions nowadays after cataract surgery. Only one restriction is no head bath for a week after cataract surgery. Also one has to wear dark protective glasses to prevent discomfort from bright light and dust, but that also when one goes out of the house in the sun. At home, no such glasses are required. Also eye drops have to be applied for 3-4 weeks as necessary.

One can watch TV, do computer work, read papers or books, go for a walk from the same day of surgery. Ladies can do cooking etc also. No restrictions while sleeping also. For reading one can use the old glasses to read with the other eye. Any other doubts, feel free to ask your doctor.

Q: Will I require glasses after surgery?

A: Most of the times you will be able to most of your work without glasses. However, for fine distance and near work, glasses may be required. This differs from patient to patient. This is because the doctor is only human and cannot replicate nature’s precision.

Q: Is cataract surgery permanent?

A:Yes. It is not possible to get another cataract once it has been removed. However,approximately 10% of patients may become aware of a gradual blurring of vision some months or even years after the surgery due to thickening of the lens capsule that supports your artificial lens. If this occurs, clear vision is usually restored by a simple laser treatment,called a capsulotomy, which can be performed during a short visit to the clinic.

Eye problems in children

What are the common eye problems in children?

1. Refractive error (glasses) is commonest Amblyopia (Lazy eye)

2. Allergic Conjunctivitis

3. Squint

4. Cataract

How will I know if my child has glasses or no?

1. Child rubs his/her eyes

2. Goes close to the tv or holds things close

3. Does poorly/ not take interest at school and visual activities

4. Refuses to read/ study

5. Squinting of eyes

6. Headache and eye strain

7. Rarely child may complain of reduced vision

8. Rarely recurrent stye/ chalazion (boils on the lids)

What if my child has refractive error (glasses)?

1. Child just has to wear glasses as advised by your doctor

2. There is nothing wrong with the eye if the child has glasses

3. Plus powered glasses may go after some time

4. Minus powered glasses (distance glasses) are generally for life and may increase over time due to child’s growth

5. Watching too much TV/ mobile/ tablets etc do not give your child a refractive error or glasses

6. Refractive errors are hereditary or due to growth of the child

7. Refractive errors will stabilise once the childs growth is completed at around 18-21 years of age

What is amblyopia or lazy eye?

1. If both eyes have high power

2. If difference in the power between two eyes is more

3 If any or both eyes have a squint

4. If any of the above conditions not treated with appropriate glasses or surgery

Then,

a. The part of brain related to eye(s) does not develop

b. This causes blurred/ decreased vision in one or both eyes even though the eye is otherwise fine

Refer to ‘’Amblyopia’’ brochure for further details

Your child rubs his eye frequently and they become red. What to do?

1. Your child could be having allergic conjunctivitis

1. Your child could be having allergic conjunctivitis

2. Quiet common in childhood like tonsils

3. Unfortunately recurrent till 12-15 years of age, then subsides on its own

4. Treated with medications under medical supervision

- In severe cases mild steroids are given to reduce severity of attack</li>

- Please do not self-medicate since the drugs can have side effects like

- cataract and glaucoma if misused

- In mild cases or recurrences, other anti-allergics are given, which are relatively safer

- Lubricants or tear substitutes are given to wash away the allergens (things that cause allergy)

- and toxic matter formed by the allergic reaction. They are very safe and can be used on a SOS basis

5. Rarely your child could be having a refractive error (glasses) also

Your child has a squint. What to do?

2. Some squints get corrected just by wearing appropriate glasses

3. Some squints are not significant and can be safely observed

4. Some squints require surgery especially if causing lazy eye

5. Your doctor is the best judge in such a condition

Refer to “Strabismus” brochure for further details

My child watches TV all day, plays mobile all day. Will it harm his eyes’’?

– God has given eyes to see

– Using them doesn’t harm them

– Excess of anything is bad

– She/he won’t get glasses due to this

Do eye exercises help? Will my child’s number or squint reduce with exercise ?

– They do not help in reducing your child’s number or squint

Does my child require any special diet like carrots, spinach etc?

– The normal balanced diet we give our children is sufficient

– Carrots, spinach etc are good but not of any special benefit for the eyes

Diabetes and Diabetic Retinopathy

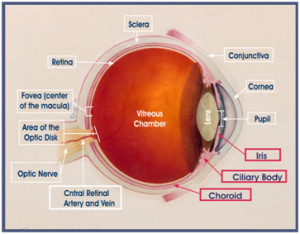

Q: What is vitreous?

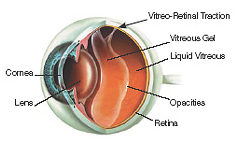

A: The eye is a ball of about 2.5cm diameter. The cornea and lens at the front of the eye focus light onto the retina (Figure 1). The eye is similar to a camera, with the focusing lenses in front, and the light sensitive film (retina) lining the back. The vitreous is the clear gel (jelly) which fills up the space inside the eyeball, behind the iris (the blue or brown part) and the lens.

Q: What is retina?

A: Retina lines the inside of the wall of the eye. The retina transforms light into electrical impulses, which travel up the optic nerve to the brain.

Q: What is macula?

A: The macula is the central part of the retina. It is a small, specialized area in the middle of the retina and is responsible for our ability to see fine detail. This central vision is the vision we use for reading, driving, recognising faces, threading needles and other fine detailed work. The remaining part of the retina is responsible for our side vision, also known as peripheral vision. This is our mobility vision, allowing us to get about and to maintain our independence.

Q: How do we see?

A: Our eyes are like a camera with a lens system at the front of the eye, and the retina, like a photographic film, lining the inside wall of the back of the eye. Light passes through the cornea, pupil and lens and is focused on the light sensitive retina to form an image. Messages are sent via the optic nerve to the brain for processing.

Q: How does diabetes affect the eye?

A: Diabetes can affect the eye in several ways. It can damage your sight by causing cataract, but also more importantly, by causing diabetic retinopathy.

Q: What is diabetic retinopathy?

A: Diabetic retinopathy is a potentially blinding complication of diabetes that affects up to a half of diabetics to some degree. At first you may notice no changes in your vision, but diabetic retinopathy can worsen over the years and damage your sight. With timely treatment, over 80% of people with advanced diabetic retinopathy can be prevented from going blind. We recommend every diabetic have an eye exam through dilated pupils at least every two years.

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetics are at risk of diabetic retinopathy. Pregnancy is a relatively high risk period for worsening of diabetic retinopathy and close follow up during pregnancy is recommended.

Q: How does diabetic retinopathy affect vision?

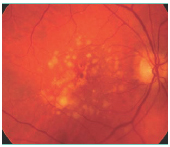

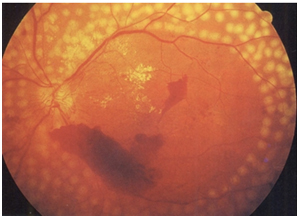

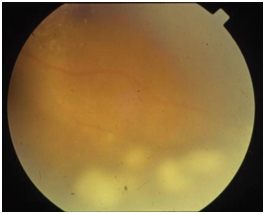

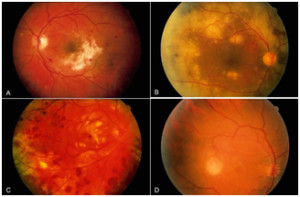

A: Diabetic retinopathy occurs when the small blood vessels in the retina become damaged by high blood sugar levels. It affects the eyes in two forms.

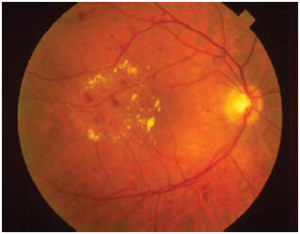

Macular oedema describes the condition where retinal blood vessels develop tiny leaks in the very centre of the retina. When this occurs, blood, fluid and lipids leak out causing swelling of the macula.

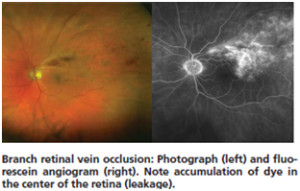

Small bleeds and areas of blood vessel leakage in an eye with macular oedema. Yellow deposits are lipid.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy describes the changes that occur when abnormal blood vessels begin growing on the surface of the retina. These new blood vessels have a tendency to bleed or cause adjacent scar tissue growth. Leaking blood from these blood vessels can cloud the vitreous jelly that fills the centre of the eye and cause severe blurring. Scar tissue formation can lead to retinal detachment, which if left untreated often leads to blindness. If these abnormal blood vessels start growing around the pupil you can also develop a diabetic type of glaucoma, which can be very difficult to treat.

Q: What are the symptoms of diabetic retinopathy?

A: Many people with severe sight threatening diabetic retinopathy have no eye symptoms at all and therefore regular checks are required to allow treatment to be applied before it is too late.

The common symptoms are:

1) Blurred vision and difficulty reading

2) Sudden loss of vision in one eye

3) Dark spots floating around inside the eye

If you have these symptoms, it doesn’t mean you definitely have diabetic retinopathy, but you should have your eyes checked.

As part of your eye examination, you may occasionally be asked to have special imaging tests performed called OCT scans and fluorescein angiograms.

Q: How can I prevent diabetic retinopathy?

A: Unfortunately, one cannot prevent diabetic retinopathy. It is a progressive disease. Having regular eye checks every 1 to 2 years is the most important thing you can do. Good blood sugar control and blood pressure control also reduce the risk of developing advanced diabetic retinopathy. Regular physical exercise is important to control diabetes and diabetic retinopathy.

Q: What is the treatment of diabetic retinopathy?

A: In most early cases of diabetic retinopathy, treatment is not required, but ongoing observation is still needed. When required, it can be any of the 3 means, depending on the type and stage of retinopathy.

Laser surgery is the mainstay of diabetic retinopathy treatment. It is done for both macular oedema and Proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy requires up to 3 sittings of laser on 3 different (could be consecutive) days. This is usually a clinic procedure that means you don’t need to go to the operating theater. The laser is applied through a contact lens system. During the procedure you will see bright lights in your vision. For the rest of the day your vision may be blurred and the eye may feel a little bruised.

Laser treatment has its limitations. The main aim of laser is to maintain existing vision and prevent further vision loss. Occasionally bleeding can happen following the procedure, in proliferative diabetic retinopathy due to the disease itself and not due to laser.

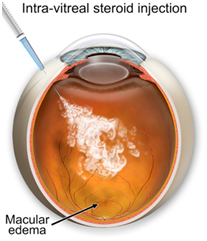

Injections into the eye of various drugs are required to stabilize diabetic retinopathy mainly macular oedema. This sometimes has to be repeated and may be required in conjunction with laser treatment or vitrectomy surgery. Presently, injections with laser are the preferred treatment option for macular oedema, with results better than laser alone.

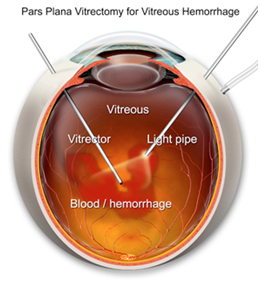

Vitrectomy surgery is occasionally performed on eyes with advanced diabetic eye disease. If you have a lot of blood in the vitreous jelly, removal of the jelly with a vitrectomy will clear away the cloudiness in your vision. Sometimes this surgery is also performed if you have a retinal detachment associated with your diabetic retinopathy. A vitrectomy is usually a local anaesthetic procedure, which means you will be awake at the time, with the eye fully numbed.

Q: What are the injections to be given in the eye? Are they painful? What are the risks?

A: Currently we have three options in injections.

1. Treatment with Lucentis or (Accentrix in India)(Ranibizumab)

There is a new treatment that is effective in improving vision and clearing macular edema in diabetic retinopathy. It is injection of Lucentis into the eye once a month for at least six months. Lucentis is an antibody against the molecule that causes macular edema and the growth of abnormal vessels (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor or VEGF)

Vision improvement is rapid and seen on average, by seven days. Patients are treated with three to six monthly injections. After six months it may be possible to stop the treatment, but this varies from patient to patient. If the vision is down, we usually restart treatment immediately. If vision is good and there is no macular edema, observation may be continued.

2. Treatment with Avastin (Bevacizumab)

This is another Anti –VEGF drug, which is FDA approved for treatment of cancers and has also been shown to work for macular edema. Research has proven it to be equally effective and safe as Lucentis.

We prefer to use Lucentis when possible and patient permitting, because it is the drug that has been shown to work in large clinical trials and is prepared under strict and specific FDA guidelines for use inside the eye.

3. Treatment with Steroids

They are used only in diabetic macular edema.

Intraocular steroid injections like triamcinolone (IVTA) and Ozurdex are another treatment option. The duration of action is much longer and so the need for less frequent injections. In some cases like persistent macular edema, they are more effective than anti-VEGF injections.

However there is a significantly higher risk of glaucoma and cataracts in patients given steroid injections, especially if they are repeated.

Ozurdex is a long acting steroid implant, which contains a different steroid, dexamethasone. The duration of action is for about 4 months. The risk of cataract and glaucoma is marginally less than triamcinolone (IVTA).

While Lucentis is a better, safer option for most cases, sometimes steroid treatment by itself or in combination with Lucentis may be warranted.

Both Avastin and Lucentis are used in diabetic macular edema as well as in proliferative diabetic retinopathy, especially prior to surgery.

All the above injections are given under topical anaesthesia. So they don’t cause any pain. All the injections have a risk of eye infection and retinal detachment. Thankfully these are very rare. The additional risks with steroid injections are mentioned above.

Q: What is end result of diabetic retinopathy?

A: Patients who have milder disease and have got treatment at appropriate time end up having moderate to good vision. Patients with advanced disease, in spite of treatment have moderate to poor vision depending on the blood supply to the retina and macula and health of the retina.

Epiretinal Membrane

Q: What is Retina?

A: The retina is a thin delicate tissue that lines the inside of the back of the eye. It is nerve tissue that senses light that shines into the eye, converts the light into an electrical signal and sends this signal through the optic nerve to the brain, which then processes the information resulting in sight. The macula is the very central area of the retina that gives us sharp central vision and reading vision, as well as most of our colour vision.

Q: What is an epiretinal membrane?

A: An epiretinal membrane is a thin sheet of fibrous tissue that can develop on the surface of the macula. When a membrane develops on this very thin, delicate macular area of the retina it acts like a film through which it is harder to see than normal. Furthermore, it may contract just as scar tissue does, pulling on the retina and distorting it, causing not only distortion of the vision due to distortion of the macula, but also causing the retina to become swollen and work less well. Because it is often the distortion of the macula that is the most obvious feature of this problem, it is sometimes also called a macular pucker, premacular fibrosis, surface wrinkling retinopathy or cellophane maculopathy.

Q: What causes an epiretinal membrane?

A: In most cases an epiretinal membrane is idiopathic, that is it develops in an eye with no history of any previous problems. It is not due to anything the afflicted individual has done, but instead is caused by natural changes in the vitreous gel overlying the macula that cause normal biological cells derived from the retina and other tissues within the eye to become liberated into the vitreous gel and eventually settles onto the surface of the macula. In some cases these cells may begin to proliferate into a “membrane”.

In many instances this membrane remains very mild and does not have any significant effect on the macula or the person’s vision. In other cases however, the membrane may slowly become more prominent, eventually creating a disturbance in the retina that leads to visual blurring and/or distortion in the affected eye, particularly if the membrane contracts.

However, an epiretinal membrane can also develop if cells are liberated into the eye by a previous problem, such as a retinal tear or detachment, trauma, inflammatory disease, blood vessel abnormalities, or other conditions. These are called secondary epiretinal membranes; they have the same effect on vision as the idiopathic type and are treated in the same way.

Q: How does an epiretinal membrane affect vision?

A: Many epiretinal membrane are mild and have little or no effect on vision. However, if the epiretinal membrane grows more prominent and contracts, causing mechanical distortion (“wrinkling”) of the macula , blurring and/or distortion of the central portion of vision in the affected eye may occur and may get slowly worse over time.

An epiretinal membrane does not make an eye go completely blind. It typically affects only the central area of vision and does not cause a loss of the peripheral (side) vision.

Q: Is an epiretinal membrane the same as macular degeneration?

A: No! An epiretinal membrane and macular degeneration are completely different conditions affecting the retina

Q: Is there treatment for an epiretinal membrane?

A: Yes. An epiretinal membrane can be treated with surgery. However, not all epiretinal membranes require treatment. Treatment is unnecessary if the epiretinal membrane is mild, stable and having little or no effect on vision. Only cases in which the membrane is causing problems require consideration of surgery. However, it an epiretinal membrane is getting worse it is better to remove it sooner rather than later, as severe mechanical distortion of the macula may cause permanent changes that removing the membrane may not improve or only improve to a limited extent.

There is no other treatment apart from surgery for an epiretinal membrane.

Q: What is epiretinal membrane surgery like?

A: The surgery for a epiretinal membrane is called a vitrectomy. This surgery is usually done as a day (outpatient) surgery using a local anesthesia, and takes up to an hour. The surgery consists of making very small ports through the white part of the eye (the sclera) 3 mm behind the edge of the cornea. Newer surgical techniques and instrumentation allow the surgeon to perform the surgery through tiny “self-sealing” incisions that do not require sutures. This new technique allows faster healing of the eye with minimal or no post- operative ocular irritation.

While looking into the eye through a microscope the surgeon can use a variety of very specialized instruments placed through these incisions to work within the eye. The vitreous gel is first removed as is the posterior hyaloid membrane which is at the back of this gel. This holds the gel together like the skin of a balloon filled up with water; removing it also removes any floaters that one may have. The vitreous gel is then replaced with a specially designed saline solution. The surgeon can then “peel” the epiretinal membrane from the surface of the macula. Sometimes the surgeon also peels a very thin membrane (the “internal limiting membrane of the retina”) from the surface of the macula which can become puckered by the epiretinal membrane sitting on top of it. Steroid treatment or air are commonly placed inside the eye to hasten the rate at which the retina recovers from having been distorted by the membrane, and laser and freezing (cryotherapy) treatment is usually also used to secure the peripheral retina in place.

Q: What is the postoperative care like after epiretinal membrane surgery?

A: A patch is worn over the eye until the morning after surgery. Eye drops (an anti-inflammatory and an antibiotic) are then used several times each day for up to 4 weeks after surgery. Patients can usually resume normal non-strenuous physical activities the day after surgery. How quickly the patient can drive, return to work, perform fine visual tasks, or engage in strenuous activities will vary from person to person.

Q: How much will my vision improve after surgery?

A: The amount of visual improvement will vary depending on the age and anatomic characteristics of the epiretinal membrane, how significantly the vision has become affected by the epiretinal membrane, and the presence of any other ocular abnormalities that might limit vision. It is not unusual to recover vision of 6/6 or 6/9 after successful epiretinal membrane surgery, and the distortion improves in 90% of patients. However, some individuals may have more limited improvement in vision, especially if the membrane had been there for a long time and the vision had already become very poor, and a small percentage of people may not improve very much at all even with successful surgery. It takes anywhere from 3 months to 1 year for vision in the affected eye to reach it’s maximal improvement.

Q: What complications may occur as a result of epiretinal membrane surgery?

A: Any surgical procedure carries a risk of complications and this surgery is no exception. There are 3 major potential complications of surgery:

1. Post-operative infection (endophthalmitis): This is an infection that develops inside the eye after ocular surgery. Though most infections can be effectively treated if identified at an early stage, there is a risk that an infection can create severe damage that could lead to blindness in the affected eye. Fortunately, endophthalmitis is rare, occurring in only 1 of 1000 cases.

2. Retinal detachment: Retinal detachment can occur spontaneously in an eye that has never had surgery of any type. However, an eye that has undergone surgery is at greater risk of developing retinal detachment. A retinal detachment may occur relatively soon after surgery, but may occasionally develop months or years later, and can lead to blindness if not repaired. Fortunately nearly all retinal detachments can be between 1 and 2 out of 100 cases.

3. Cataract: Cataracts, or haziness in the lens of the eye, commonly develop as a natural consequence of aging of the eye. However, a cataract will often develop or progress to a point of significant visual blurring sufficient to warrant cataract surgery more quickly after having had this surgery. This is not a concern if the patient has had cataract surgery prior to having a vitrectomy surgery.

Glaucoma

Q: How do we see?

A: The visual system is like a digital camera (the eye) connected to a computer (the brain) that makes sense of what the camera detects. The optic nerve is the “cable” that connects the eye to the brain. Nerve fibres carry visual messages from all parts of the retina, which lines the eye and detects light and colour. These nerve fibres come together at the optic disc to form the optic nerve.

Q: What is glaucoma?

A: Glaucoma is a common eye condition (or group of conditions) that can lead to blindness – in fact glaucoma is the second most common cause of blindness around the world. Fortunately if glaucoma is detected early and managed appropriately in nearly every case blindness is preventable. Glaucoma is most often controlled with eye-drops, but laser, tablets and surgery are also used in its treatment.

Glaucoma is a disease of the optic nerve, the “telephone cable” that carries visual information

from the eye, where images are captured, to the brain, the computer that makes sense of what is seen. Most cases of glaucoma proceed very slowly as optic nerve fibers are gradually lost.

Q: What causes glaucoma?

A: Intraocular pressure (IOP) (pressure inside the eye) normally ranges between 10 and 20 mm of Hg. Rise in this intraocular pressure reduces the blood circulation to the optic nerve and damages it. Other causes of reduced blood supply to the optic nerve including age, hypertension (raised blood pressure), diabetes mellitus, hyperlipedemia (raised cholesterol), heart disease, smoking and drinking can contribute to glaucoma.

Q: Who can get glaucoma?

A: Babies, children and young adults can get glaucoma, but these types of glaucoma are rare. Glaucoma becomes much more common as we get older, occurring in 2% of the population over 40 but in as much as 11% of the population over 80. As mentioned above people having other illnesses have a higher risk of developing glaucoma. Glaucoma may also follow on from other eye disease or eye injury. People with a family history of glaucoma have a higher risk of developing glaucoma.

Q: What are the types of glaucoma?

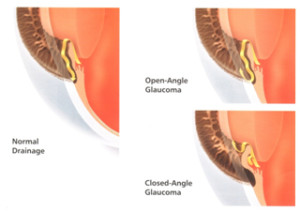

A: There are many different types of glaucoma. The two main types of glaucoma are Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG) and Closed Angle Glaucoma (CAG).

Q: What is Open angle glaucoma?

A: Most people with glaucoma have forms of POAG. There is most often a family history. There is damage to the drainage system of the eye, leading to increase in IOP, leading to glaucoma.

Q: What is closed angle glaucoma?

A: The second most common type of glaucoma is Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma (PACG). There is narrowing of the drainage passage in the eye due to smaller eyeball size (as in people having high plus number) or due to thickening of lens due to cataract. This can develop very slowly, like open angle glaucoma, or can occur suddenly in the case of Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma, where the eye becomes very red and painful and vision is lost in a matter of days if appropriate treatment is not begun.

This form of glaucoma is more common in Indians/ Asians than western people due to relatively smaller eyes.

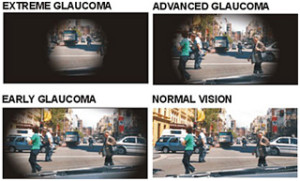

Q: What will be my complaints if I have glaucoma?

A: Unfortunately the brain does not recognise that patches of vision are missing until the damage from glaucoma is very advanced, so sufferers of glaucoma will only be aware they have a problem very late in the disease. It is for this reason that it is of the utmost importance that we all have regular eye examinations from the age of 45, earlier if we have glaucoma in the family. People go blind because they have glaucoma but haven’t realised this, often for many years.

Only in the closed angle type of glaucoma will a person have complaints. Patients will complaint of pain, redness, cloudy vision, coloured rings around lights, severe headache or even vomiting.

Q: How will I know if I have glaucoma?

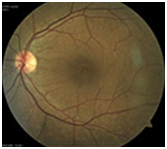

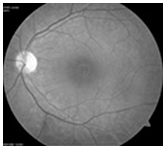

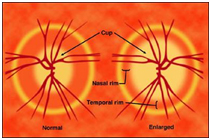

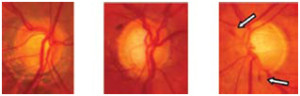

A: Normally with glaucoma there is no perceived visual disturbance nor eye discomfort to warn that someone has glaucoma. Glaucoma is detected through routine eye examinations by your ophthalmologist. Glaucoma is often associated with elevated eye pressure, and discovery of this may be how your glaucoma is detected. Glaucoma causes a characteristic type of erosion of the optic disc we call cupping, which can be seen when the back of your eye is examined.

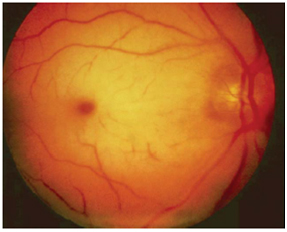

Drawings of a normal disc (left) with a normal sized cup, then a disc with ‘cupping’,enlargement of the cup due to loss of nerve tissue from glaucoma

Photos of cupped discs: in the third disc small disc haemorrhages also typical of glaucoma can be seen

Q: What is visual field testing?

A: Glaucoma causes loss of visual field, patches of one’s vision. This is detected by visual field

testing. Monitoring the visual field is particularly important to ensure that glaucoma is controlled

and not getting worse – most people with glaucoma will have field tests once a year.

Q: How to manage glaucoma?

A: Your ophthalmologist will assess and then usually treat your glaucoma. As well as asking about past eye problems and your general health, and examining your eye, your ophthalmologist will establish your glaucoma diagnosis and a treatment plan doing some or all of the following:

- establish at what level your eye pressures are running

- ensure he has a reliable, repeatable record of your visual fields

- measure your corneal thickness (pachymetry)

- record your optic disc appearance with stereo photos

- measure your nerve fibre layer thickness with the OCT

Management of glaucoma is all about detecting that glaucoma is present or not. It can take up to a year to confirm whether a patient has glaucoma or not. Till then a patient is treated as a glaucoma suspect.

This is followed by monitoring the patient to detect whether the disease is controlled, or that more damage is occurring. This is done in several ways. It is important to examine the patient’s optic discs for further cupping or disc haemorrhages which are indications of progressive glaucoma. For many discs however only big changes can be detected.

Visual field testing is another important way to monitor glaucoma, but field loss occurs relatively late in the disease, and even good subjects will have variable field results depending on how tired they are, and how well they can concentrate on this demanding test.

Q: What is OCT?

A: The OCT is a relatively new, very sophisticated machine that can actually measure the thickness of the nerve fibre layer at the back of the eye, down to microns (thousandths of a millimeter). We can compare an individual’s OCT result to normal references, and in particular, to the individual’s test results from previous years, to see if change has occurred. For the patient the test is simple and painless, rather like having a photograph taken. It is however still a supporting test for visual fields, which is still the gold standard.

Q: What is the treatment of glaucoma?

A: At present the only way we can treat glaucoma is by lowering eye pressure. If we get the eye pressure down to a safe level, in almost all cases of glaucoma we will halt the disease, or at least slow it down so that significant vision impairment does not occur in the patient’s lifetime. The level of pressure that is safe is different for each patient, so we set “target pressures” for each individual. (Generally speaking, the lower the eye pressures the better).

1. Eye drops: Most glaucoma patients instill eye drops to keep their eye pressures at a safe level. A patient may be on one, two or more different glaucoma eye drops. These medications are for lifetime or as instructed by your ophthalmologist.

2. Laser treatment

a. Laser trabeculoplasty is a very safe and generally painless way to treat glaucoma and should be considered for all newly diagnosed cases of glaucoma. Successful laser treatment can keep the eye pressure down for a few years without requiring eye drops. Eventually patients end up applying eye drops. (The laser used is very different from the laser used to allow people to manage without glasses.)

b. Laser peripheral iridectomy is a safe and painless way of trying to prevent angle closure glaucoma in patients at risk for the same. However it is still a temporary measure as compared to early cataract surgery.

c. Laser iridoplasty is to treat patients with plateau iris syndrome (a form of narrow angle glaucoma)

3. Surgery (trabeculectomy) is also used to treat glaucoma: it is employed when the eye pressure cannot be controlled by drops and laser, and when patients cannot tolerate eye drops (or manage to get them in regularly) or in advanced glaucoma. It is rarely done nowadays.

4. Early Cataract Surgery is recommended in patients with narrow angles or chronic angle closure glaucoma, since it permanently opens up the angle and also reduces the IOP to some extent.

5. Combined cataract and glaucoma surgery is done in certain cases as required.

6. End stage Glaucoma where in patient does not much vision and pressure is not controlled with medications, a special form of laser called Diode Cyclophotocoagulation is done to keep eye pressures down. Also Anterior Retinal Cryopexy (ARC) may be required under local anaesthesia for neovascular glaucomas (glaucomas caused due to diabetes/vein occlusions).

7. Repeated injections in the eye may be required before laser or ARC can be done to prevent neovascular glaucoma.

8. Enucleation (removal of the eyeball) may be rarely required in painful blind eyes due to glaucoma.

Blood pressure, diabetes and lipid (cholesterol) control, regular exercise, avoiding smoking and tobacco and improving overall health also helps control glaucoma.

Q: What is the course of glaucoma?

A: Having glaucoma means that you must have a life-long association with your ophthalmologist. The disease can be controlled but not cured, and it is essential that patients are seen regularly (for most this is six monthly). Typically glaucoma is well controlled for a number of years but then at a follow-up visit it is found that control has been lost, for instance that the visual field is worse, and that a change in treatment is necessary. It is the ophthalmologist’s, and the patient’s responsibility to make sure that patients do not become “lost to follow-up”.

Macular Hole

Q: What is retina?

A: The retina is a thin delicate tissue that lines the inside of the back of the eye. It is nerve tissue that senses light that shines into the eye, converts the light into an electrical signal and sends this signal through the optic nerve to the brain, which then processes the information resulting in sight.

Q: What is macula?

A: The macula is the very central area of the retina that gives us sharp central vision and reading vision, as well as most of our colour vision. The fovea, the central area of the macula, is the thinnest and most fragile section of the retina.

Q: What is a Macular Hole?

A: A macular hole is a defect in the macular area, which is the central area of the retina. It is in the foveal area that a macular hole can develop. If a macular hole does develop, this small tear or hole then expands with time, letting fluid pass under the retina, causing enlargement of the blur. This process eventually becomes stable, but seldom improves without treatment. A macular hole does not lead to total loss of vision, but usually does lead to legal blindness in the affected eye if untreated.

Q: What causes a macular hole?

A: The most common cause of a macular hole is an anatomical change occurring spontaneously between the clear vitreous gel of the eye, and the macula, creating a small tear or hole in this delicate area of the retina (which expands over time).

These are naturally occurring changes, not caused by the individual and anything they have done (or neglected to do). For a small percentage of people, these natural changes become pathological, resulting in mechanical stresses in the macula that may cause a hole to form. Generally called an idiopathic macular hole, this kind of hole is most common in individuals over 50 years of age.

On the odd occasion, an eye subjected to severe blunt trauma can develop a macular hole. A very small percentage of people with retinal detachment are also affected by a macular hole, as are some conditions that cause severe edema (swelling) of the retina. These types of macular holes occur mostly in people under 50 years of age, are not widespread, and can be differentiated without difficulty from the more common idiopathic macular hole.

Q: How is a Macular Hole treated?

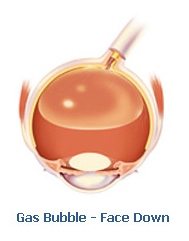

A: Surgery is the only treatment available, with a success rate of 90-95%. Vitrectomy is a procedure where the majority of the vitreous gel is removed from the eye. A large gas bubble is placed in the eye, flattening the edge of the macular hole. This bubble goes away by itself after several weeks. For 90-95% of patients, this process will lead to the macular hole disappearing. 85% will experience vision improvement, if the hole does disappear.

As with any surgery, it does not work for every patient, with the most likely aspects that predict success being the size of the hole, duration of symptoms, and original vision quality. Depending on vision prior to surgery, 60-85% will achieve driver’s license level of vision after surgery. Your Eye Doctor will discuss your personal situation and prognosis with you. In general terms the earlier the macular hole is detected and treated, the better the odds of success.

Q: How does a macular hole affect vision?

A: A macular hole affects the central element of vision, resulting in a loss of sharp, directly-in-front vision, and reading vision, in the affected eye. In the early stages, when the hole is small, vision is usually only slightly blurred or distorted. Vision progressively gets worse over a number of weeks or months, as the hole enlarges. Generally, the hole enlarges to the stage where the affected eye can only see the larger letters of a visual acuity chart. A macular hole does not bring about complete blindness as it affects only the very centre of vision, therefore not resulting in any loss of the peripheral (side) vision.

Q: Are macular holes and macular degeneration the same?

A: No – macular degeneration and macular holes are entirely different conditions, but both do affect the retina.

Q: What is macular hole surgery like?

A: Surgery to treat a macular hole is called a vitrectomy. This is usually a day-stay (outpatient) procedure performed at our centre, using local anaesthesia, and taking approximately one to two hours.

An operating microscope is used to see the retina and other structures inside the eye, and tiny incisions (under a millimeter in length) are made in the sclera (the white of the eye). Special instruments are then inserted through the incisions into the vitreous cavity to work within the eye.

Vitreous gel is removed from the eye, and replaced with a clear saline solution – such fluid comprises 99% of the natural vitreous fluid. The surgeon then typically peels a very thin membrane from the surface of the macula surrounding the macular hole.

Lastly, a gas bubble that completely fills the vitreous cavity is inserted to replace the saline solution. This synthetic gas is absorbed over time and replaced with the eye’s natural fluid called aqueous. A laser and freezing treatment is usually also used to secure the peripheral retina in place. Stitches are not normally required.

Our Center offers state-of-the art facilities for day stay eye surgery. You’ll enjoy quicker recovery and less disruption to your everyday activities.

Q: What is the post-operative care like after macular hole surgery?

A: A patch must be worn over the eye until the morning after surgery, and eye drops that facilitate healing are then used several times each day for 4 weeks. If possible, we ask people to position face down for five days immediately following the operation, but don’t worry if you can’t. The face down position permits the gas bubble to press firmly against the macular hole, which may increase the chance of the hole closing well, although the success rate is already 90 to 95% without doing this.

Q: After surgery, what improvements can I expect to my vision?

A: The extent of visual improvement will vary, depending on the macular hole successfully closing, the age and anatomic characteristics of the macular hole, and any other ocular abnormalities that might affect vision.

Most patients recover vision of 6/6 or 6/9 after successful macular hole surgery; however, some have more limited progress in vision improvement, and a small number of individuals may not improve much at all, even with successful surgery. Your Doctor will discuss in more depth about what you can expect and the possible outcomes with you, prior to surgery.

Q: When can I expect to see results?

A: It can take between 3 months and 1 year for vision in the affected eye to improve to it’s utmost potential. Patients who have had a macular hole for less than a year or two are much more likely to have an improvement in vision after this surgery. Those who have a macular hole for longer are less likely to notice an improvement.

Q: What are the possible complications of macular hole surgery?

A: As with any surgical procedure, there are risks of complications and macular hole surgery is no exception. Although the risks are very low, the three main potential complications of macular hole surgery are:

- Retinal detachment: Although retinal detachment can occur suddenly in an eye that has never had surgery of any type. After surgery however, an eye is at greater risk of developing retinal detachment. A retinal detachment can happen a short time after surgery, but occasionally develops months or years later, and if not repaired, can lead to blindness. Fortunately, nearly all retinal detachments can be repaired with surgery, and the frequency of retinal detachment after macular hole surgery is between 1 and 2 out of every 100 cases.

- Post-operative infection (endophthalmitis): This infection can develop inside the eye after any ocular surgery, causing damage that could lead to blindness in the affected eye. Fortunately, most infections can be successfully treated if recognized at an early stage, and having endophthalmitis is actually quite rare, occurring in only 1 out of every 1000 cases.

- Cataract: Cataracts (haziness in the lens of the eye) generally develop as a natural consequence of aging. However, an existing cataract can develop or progress to a point of considerable visual blurring after surgery, enough to justify cataract surgery in most eyes within a year of having a vitrectomy. This is not the case if the patient has already had cataract surgery before having a vitrectomy surgery.

Posterior Vitreous Detachment and Retinal Detachment

Q: What is vitreous?

A: The eye is a ball of about 2.5cm diameter. The cornea and lens at the front of the eye focus light onto the retina (Figure 1). The eye is similar to a camera, with the focusing lenses in front, and the light sensitive film (retina) lining the back. The vitreous is the clear gel (jelly) which fills up the space inside the eyeball, behind the iris (the blue or brown part) and the lens.

Q: What is retina?

A: Retina lines the inside of the wall of the eye. The retina transforms light into electrical impulses, which travel up the optic nerve to the brain.

Q: What is Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD)?

A: This occurs with age changes in the clear vitreous gel. Parts of the gel become liquid, pushing the remains of the gel forward, a condition called posterior vitreous detachment.

Q: What are floaters?

A: At the time of PVD, opacities frequently form at the liquid-gel interface. These are seen as floaters.

Q: Are floaters something to worry about? Will they reduce my vision?

A: They are common, and harmless in themselves. They don’t reduce your vision. However, with this degeneration in the vitreous, there is sometimes associated pulling on the retina, as in places the vitreous is adherent to the retina.

Q: What are flashes?

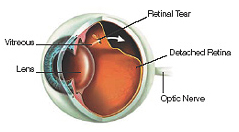

A: Pulling on the retina causes the sensation of flashes. You can see them even when the eyes are closed and more on moving the eye.If this pulling is severe enough, a hole or tear may occur in the retina. Then liquid vitreous may pass through the hole, peeling the retina off the back wall of the eye, which is a retinal detachment.

Q: What to do if you have floaters and/or flashes?

A:

- If you have had occasional floaters for years, don’t worry. The chance of retinal detachment is small.

- If you suddenly notice floaters, or experience at sudden increase in floaters, you should have your eyes examined promptly. This examination is to search for any retinal tears.

- If you develop flashing lights, seen usually at night, again you should have your eyes examined promptly. Flashing lights mean pulling on the retina and the risk of detachment is significant. However there are other possible causes of flashes, one of which is migraine. Nevertheless the sudden onset of flashes demands prompt examination of the retina. Floaters and flashes are warning symptoms which demand prompt examination, but most people who experience them never develop a retinal detachment.